In many cities worldwide, children often play on streets, which act as spaces for movement, leisure, and socialisation. However, street designs rarely reflect these functions, especially for children, whose physical health, social development, and independence are shaped by how they interact with their environment. As urban populations grow, it’s crucial to design cities that prioritise children’s well-being, considering they make up one-seventh of the global population (1.18 billion children).

As cities grow, many urban environments become unsafe for children, particularly in the Asia-Pacific region, where a lack of child-friendly spaces, safe transport, and proper design restricts their mobility. Safety concerns, such as traffic accidents and “stranger danger,” have led to increased parental supervision, limiting children’s opportunities for independent exploration, physical activity, and social interaction. Young children face significant challenges in navigating cities, with road safety being the most urgent. Traffic and pollution are global challenges according to a report by Arup, affecting children’s physical and mental development and hindering independent mobility.

Road traffic injuries are the leading cause of child deaths worldwide with 60,000 children dying in India, as per data published by WHO, driven by high vehicle speeds, congestion, and inadequate pedestrian infrastructure. In many cities, broken or absent sidewalks and distant essential services discourage walking or cycling, limiting children’s opportunities for physical activity and cognitive development. Poor street design and excluding caregivers from city planning decisions makes them hesitant to let children play or explore outdoor activities, further restricting their independence. Sprawling cities encourage car-dependency, increased traffic and pollution, inducing fear for caregivers. While overly dense high-rise living can lead to isolation and cramped conditions, well-designed developments can enable lively communities and enhance access to outdoor spaces. In addition to general mobility challenges, gender-based restrictions disproportionately affect girls, particularly in communities where societal norms require them to stay closer to home. This limits their freedom to move and engage in public life, education, and social activities, contributing to higher dropout rates among girls compared to boys.

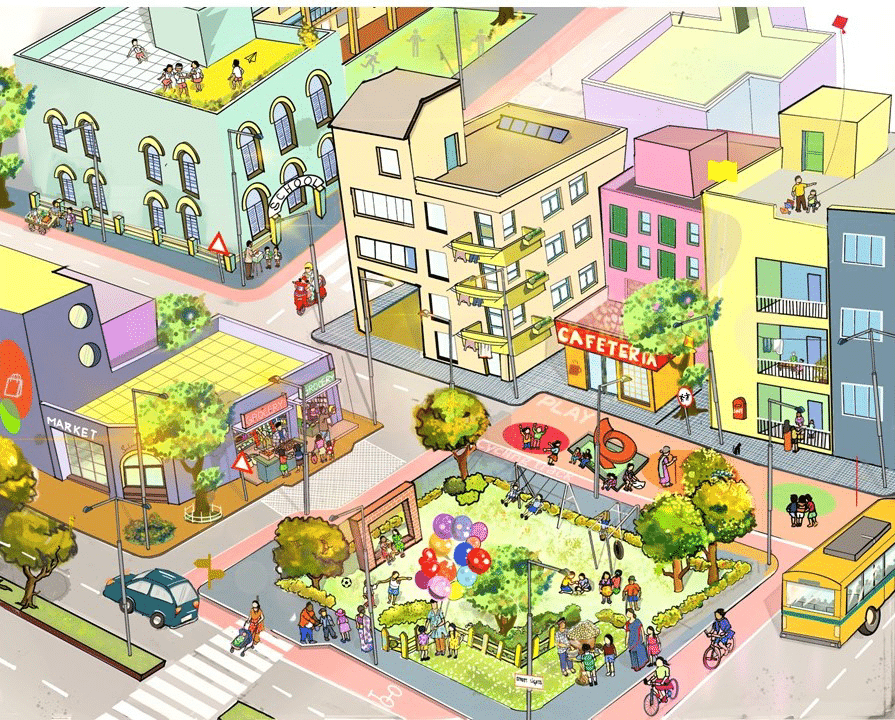

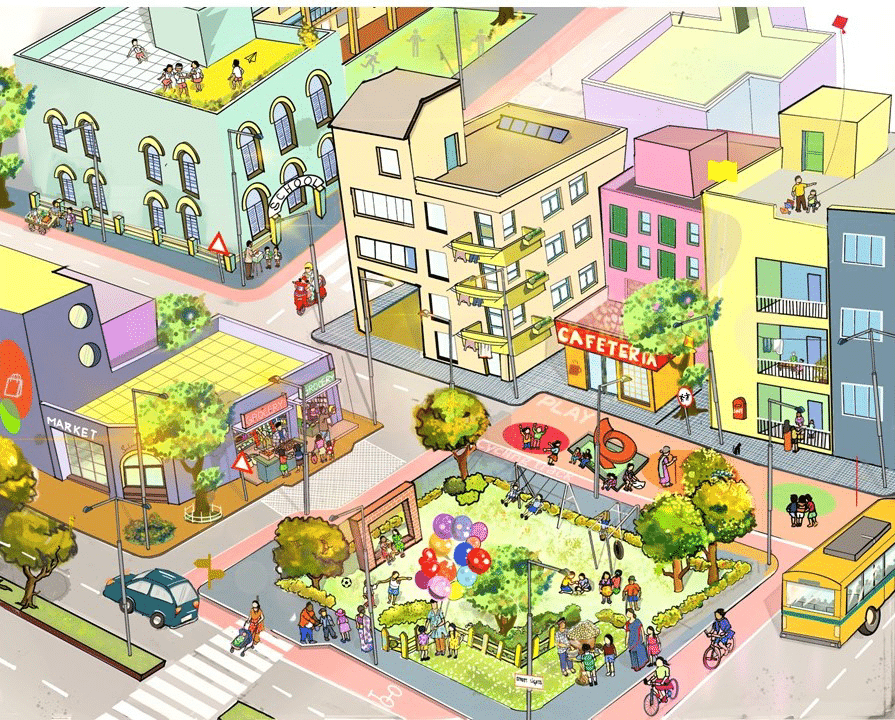

To create cities that are truly child-friendly, we need to rethink how urban spaces are designed, shifting the focus from cars to pedestrians and cyclists. This means prioritizing safety and accessibility for children. Key “traffic-calming” measures like speed bumps, traffic circles, and raised crosswalks should be provided near schools, parks, and playgrounds to slow down traffic. Beyond just safety, we can make the city more fun and engaging by adding playful elements, such as interactive bike stands, playgrounds along bike routes, and dedicated bike parks, all of which encourage kids to be more active and explore their surroundings. Enrique Peñalosa, the former Mayor of Bogotá, once described children as “indicator species” for evaluating a city’s overall livability and walkability. By designing compact, mixed-use neighborhoods, we can shorten the distances kids need to travel, making it easier for them to navigate the city on their own.

In 2018, Urban 95 organised a community walk in Ciudad Bolívar, while Bogotá’s “Ciclovía” programme serves as a successful model by closing streets to cars, creating safe spaces for children and families to walk, cycle, and play. These initiatives promote physical activity and transform the city into a vibrant, child-friendly space. Similarly, in Japan, children as young as six navigate their neighborhoods independently, aided by infrastructure designed with their needs in mind. For example, the “Kodomo 110-ban” system allows children to seek refuge in designated emergency houses if they feel unsafe, providing an additional layer of security and trust in the community. Bogotá’s System of Care Blocks is a global model for how cities can effectively address equity challenges and improve resident well-being.

Udaipur’s walled city, with its dense settlements and unorganised commercial areas, saw the Udaipur Municipal Corporati on (UMC) join the global Urban 95 program in 2019 to become an Infant, Toddler, and Caregiver (ITC)-friendly city. Through the programme, Nayion Ki Talai Chowk was transformed with tactical solutions, including Aganwadis, schools, and religious spaces, increasing pedestrian footfall. Today, the area is a vibrant space where children play traditional games and parents gather, fostering community cohesion.

For children under the age of five, mobility is often dependent on caregivers. Whether in strollers, carried by adults, or in cars, caregivers face significant challenges when navigating public transport systems. Overcrowded buses, poorly designed waiting areas, and long wait times make it difficult for caregivers to travel with young children. Furthermore, poor first and last-mile connectivity — i.e., the walkable distance to transport stops — compounds the problem.

To improve mobility for children and caregivers, public transport systems must be designed with caregivers in mind. Public transport should offer seating for caregivers with children, stroller spaces, bus stops should be well-lit and sheltered, and transport hubs should be connected by safe, pedestrian-friendly walkways. In Bogota, the city’s 8 million residents including 3.6 million unpaid caretakers, mostly women, with 1.2 million engaged in full-time care work in Care blocks these features ensure that children and caregivers can move around the city more easily and safely.

Cycling is an essential mode of active mobility for children, and safe, dedicated bike lanes should be integrated into city planning. Separated bike lanes, away from vehicular traffic, allows children to cycle independently and explore their cities safely. Providing bike racks, and sharing knowledge on safety cycling in schools can also help encourage children to take up cycling as an independent mode of transport. Walking, too, is an important aspect of urban mobility for children. Well-maintained sidewalks, safe crossings, and pedestrian-friendly streets help children and caregivers move around independently.

Introducing programmes in schools and communities to teach children how to navigate city streets safely is essenti al. This should include how to cross streets safely, how to use traffi c signals, and how to behave around vehicles. Encouraging a cultural shift in how we view children’s independence is essenti al. Many parents are hesitant to let their children move independently, fearing for their safety. Public awareness campaigns, educati onal initi ati ves, and the visible success of child-friendly urban spaces can help change percepti ons and encourage greater autonomy for children.

Planning practices often overlook young children’s perspectives, limiting their presence to school premises and occasional playgrounds. Arup’s report, ‘Cities Alive—designing for Urban Childhood’ asserts that child-friendly cities offer benefits beyond well-being. Designing child-friendly citi es offers benefits like economic revitalization, improved safety, community cohesion, and environmental sustainability. A key aspect of this is involving children and caregivers in the planning process through participatory workshops, focus groups, and advisory councils. Children’s insights are crucial for designing safer, more accessible streets, public spaces, and transport systems, as they are directly attuned to the challenges they face. When children parti cipate in decision-making, it not only improves urban spaces but also instills a sense of ownership and responsibility.

Designing cities for children goes beyond just creating safe streets — it’s about creating environments that foster independent mobility, exploration, and social interaction. Child-friendly cities not only promote children’s physical, cognitive, and social development, but also improve overall urban sustainability and inclusivity. By prioritising pedestrian and cyclist infrastructure, enhancing public transport accessibility, integrating safety features, and involving children in the design process, cities can become vibrant spaces where children can thrive. Ultimately, creating child-friendly cities benefits everyone, creating safer, healthier, and more vibrant urban communities for all.

Women drivers are a symbol of economic, and social empowerment. They are also an essential part of the broader restructuring of the transport sector to facilitate not only mobility but also to attain sustainable development goals of equity and inclusion. While significant challenges exist in mainstreaming women drivers into the transport workforce, measures can be implemented at all levels to ensure an inclusive transition.

NDC Transport Initiative for Asia (NDC-TIA) is part of the International Climate Initiative (IKI). The German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (BMWK) supports this initiative on the basis of a decision adopted by the German Bundestag. It supports China, India, and Viet Nam as well as regional and global decarbonisation strategies to increase the ambition around low-carbon transport.

Safetipin is a social impact organisation working towards Building Responsive, Inclusive, Safe and Equitable Urban Systems. We collaborate with government and non-government stakeholders in using big data to improve infrastructure and services in cities.

Become a Network member by joining the LinkedIn Group: Women on the Move: Transforming Transport in Asia | Groups | LinkedIn

©Anwesha Bhattacharya

©Anwesha Bhattacharya

Anwesha Bhattacharya

anwesha.bhattacharya@safetipin.com

Shramana Ghosh

arshramanaghosh@gmail.com