This is how GIZ colleague Andrea Palma put it when she described to us Chile’s plans for implementing national climate plans. In nine interviews we talked to GIZ colleagues and ministry representatives from Chile, China, Colombia, India, Kenya, Morocco, Philippines, Uganda, and Vietnam in an attempt to identify the most important drivers and prerequisites for implementing climate measures in the transport sector. Please click here for access to the full publication.

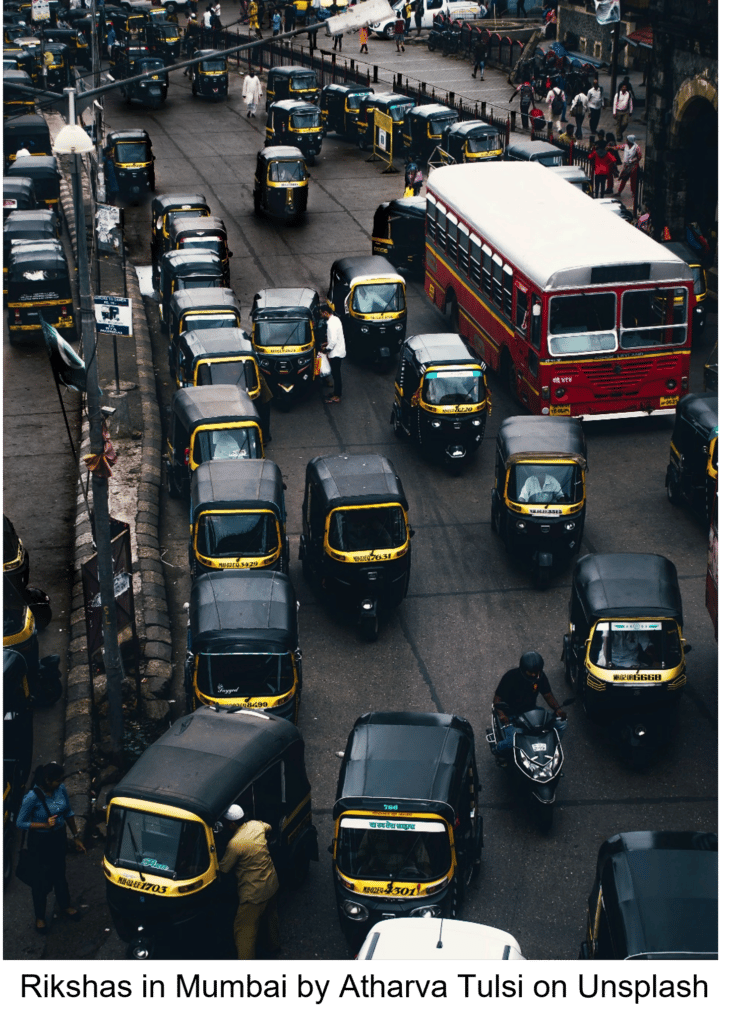

Over the last three years more than 140 new and updated NDCs have been submitted. The share of countries committing either to emission reductions in the transport sector or to other kinds of quantifiable action doubled in comparison to the first NDC generation (from 21 to 42%). The share of NDCs containing transport mitigation measures also increased, from 65% to 78%. Among the countries that we investigated, Chile, Colombia, Morocco and Uganda committed to quantifiable transport targets (e.g. Chile which plans to electrify 58% of private vehicles by 2050). All of them (except for India and the Philippines) include measures aimed at reducing emissions from transport in their latest NDC.

Now, it is time for the pledges and commitments contained in the NDCs to be translated into tangible policies and action through laws, governance structures, stakeholder ownership, inclusiveness, funding mechanisms, and accountability instruments.

Most countries have comprehensive laws on climate change and environmental protection that serve as the basis of national climate action. In Kenya, the 2016 Climate Change Act requires all ministries to establish climate change coordination units, among other sectoral requirements. In 2020, Vietnam introduced the Law on Environmental Protection, which determines the emissions reduction target for the transport sector and thus guides sectoral action. Chile’s Climate Change Law obliges all sectors to develop plans to lower emissions. Uganda approved the Climate Change Act in 2021, concurrent with its NDC revision. The legislation mandates the implementation of the Paris Agreement in Uganda and provides a basis for the implementation of NDC pledges. The Colombian Climate Action Law sets out a catalog of government actions and outlines an agenda for compliance with the Paris Agreement and carbon neutrality by 2050.

In some countries, climate laws foresee specific governance structures – such as the establishment of a climate change unit within each department of government, as is the case in Kenya. Many of these laws are comprehensive and cross-cutting in scope, obliging ministries to consider climate change in their policymaking. However, when national or regional authorities fail to back climate action with corresponding budget allocations, climate ambition may amount to so much “hot air”.

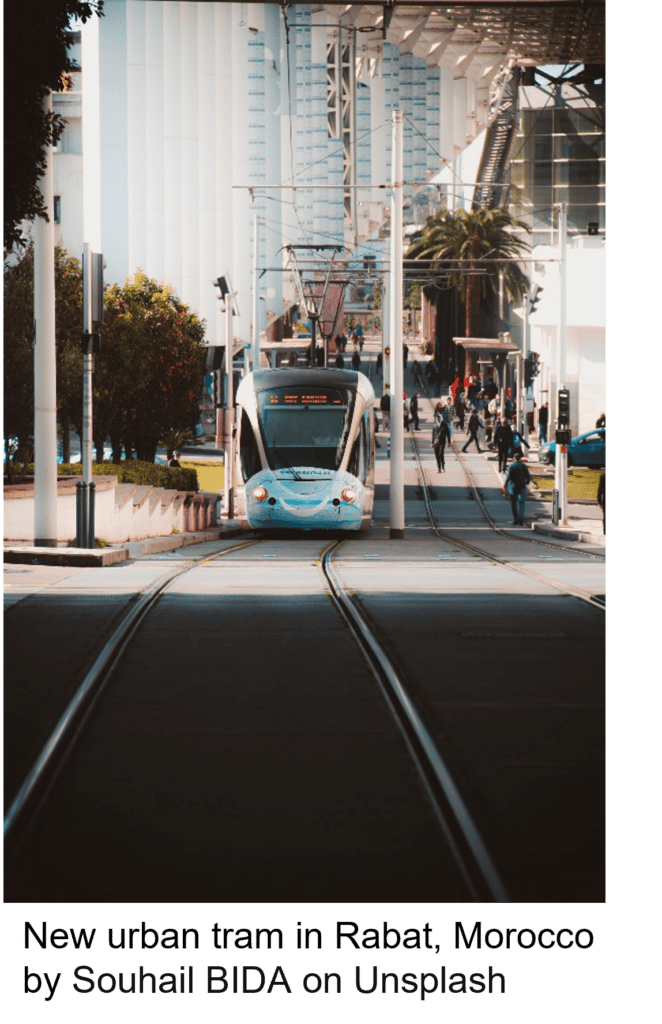

At the sectoral level, some countries have already developed strategy frameworks for transport and climate change. In Vietnam and Chile, for example, climate change laws contain binding sectoral targets and outline sectoral actions. Morocco, has included the decarbonization of transport in its Vision 2030 and energy strategy.

Translating long-term strategies and NDC-based targets and measures into real-world action requires the activation of various actors, including national, regional, and local officials, as well as stakeholders in the private sector. A comprehensive governance framework can help to harmonize the activities of actors, i.e. between federal ministries or economic sectors (i.e. horizontally) or at different levels of government (i.e. vertically).

Establishing interagency climate coordination units or setting up intersectoral teams are two possible solutions for improving vertical and horizontal coordination.

Governance approaches differ between countries. Some countries, such as Kenya, have established climate change units within each government agency, thus shifting responsibility to the agency level. Others, such as Colombia with SISCLIMA, the National Climate Change System, have created a centralized agency responsible for all steps, including the setting of targets, the development and implementation of measures, and their monitoring and evaluation. These climate change agencies can be powerful actors that drive action across sectors and at varying levels of government. However, when such agencies are not equipped with an adequate budget or the necessary political authority, they are likely to remain on the sidelines, unable to trigger meaningful climate action.

Stakeholders taking responsibility for or “owning” a set of policies or targets can be a determining factor for successful implementation. In the run-up to the second round of NDCs due in 2020–2021, sector ministries such as transport ministries became more deeply involved than in 2015 and beyond. This time, extensive stakeholder consultations that integrated the public were held in many countries, including Kenya. Still, very few NDCs mention the involvement of the transport ministry.

The infrastructure units described in the governance section have helped Chile foster ownership in its cities and regions. By contrast, India has been pursuing a very centralized approach, in which the national government assigns numerous responsibilities and targets to cities and states, without consulting them beforehand. To encourage action at the municipal level, India has developed a system in which selected cities compete with each other in terms of sustainable development.

Transport stakeholders should partake in the NDC development process from the start as it is them who have to translate NDC commitments into policies and actions. As shown, strong political obligations (e.g., from climate change laws), awareness raising and involvement in climate change discussions and competitions can incite engagement and ownership of stakeholders.

Climate change reveals – and exacerbates – existing inequalities in our societies. Accordingly, transport measures designed to reduce emissions and support adaptation must be inclusive and equitable. As the IPCC puts it, “Attention to equity and broad and meaningful participation of all relevant actors in decision-making at all scales can build social trust, and deepen and widen support for transformative changes” (2022).

Morocco, for example, has established the Economic, Social and Environmental Council (CESE). The CESE seeks to promote dialogue and debate, with the aim of encouraging societal consensus on important issues. In the past, it has recommended sustainable mobility policies to the government, based on its discussions with civil society.

The Ugandan NDC intends to assure that the updated NDC actions will be implemented through a whole-of-society approach that involves government, the private sector, academia, civil society, youth, and international development partners.

Fifty countries, almost all of them Non-Annex I countries, have indicated financing needs in their new and updated NDCs. Nevertheless, these NDCs contain little information on how implementation is to be financed.

In the past, national public and private sources of funding accounted for 98% of global transport investment. Public sources of investment (and accompanying regulations) are necessary to leverage larger streams of private funding. Economic instruments such as taxes and subsidies can be used to incentivize or discourage certain investments, sometimes while generating government revenue.

The National Planning Department of Colombia has developed a financing system that assesses how public investment measures affect climate change, including those in the transport sector. In addition, the Colombian government created a national carbon tax in 2016 to discourage the use of fossil fuels and generate revenue. These are just two of the many financing instruments that Colombia has implemented.

The Ugandan Ministry of Finance Planning and Economic Development is in the process of setting up a Climate Finance Unit. The unit will be tasked with enhancing institutional coordination and will have the capacity to design funding programs and mobilize resources for climate actions stipulated under the country’s NDC.

Regardless of whether funding comes from domestic public or private sources or from international funds (such as the Green Climate Fund), transport ministry officials need to know how to access necessary financing and how to shift funding from carbon-intensive transport infrastructure and systems to sustainable means of transport. Application processes for international funds can be tedious, time-consuming, and cost intensive, which is why many developing countries obtain much less funding than they are eligible to receive. Accessing domestic resources or implementing fiscal measures that generate revenue also require knowledge and capacities that are not always available to transport officials.

Only by using monitoring and reporting emissions and verifying reductions can the effectiveness of measures be ensured and further improved.

Kenya’s Climate Change Act (2016) requires public- and private-sector actors to develop and report GHG profiles. In 2019, the transport sector was the first sector to comply with the act’s requirement of publishing an annual climate change report that describes the transport sector’s emissions and mitigation actions.

Since 2021, Chile has been working to standardize its MRV system across all sectors in order to make them comparable and increase accountability. In Colombia, a centralized MRV system for tracking mitigation actions and emissions is in place. Compliance is mandatory, but so far there has been no follow-up. In fulfillment of the 06/ND-CP directive, the Vietnamese Ministry of Transport is currently developing an MRV system. Morocco has a national inventory system and offers training courses for ministry employees.

So far, 23 countries have set GHG emission targets for the transport sector in their latest NDC. Uganda is the only one of the assessed countries that mentions a quantified target. Sectoral targets may simplify monitoring and reporting because it is possible to track them by setting up a GHG inventory while tracking the mitigation effect of isolated mitigation measures requires the set-up of complex MRV systems.

If the world continues to release emissions at its current level, we will pass the 1.5°C limit in nine years (Global Carbon Budget 2022). Hence, there’s no time to lose: climate pledges need to be implemented now. This is no easy task, as interviewees from nine countries have made abundantly clear. Strong political will at high levels and in climate change line ministries is only one important element; the other side of the coin is (early) involvement of sectoral players at all levels.

We hope that this report inspires policymakers and climate change advocates to further increase peer learning efforts in order to adjust and improve implementation mechanisms with the goal of setting the wheels in motion for sustainable transport and a livable future.

The ‘Advancing Transport Climate Strategies’ (TraCS) project is funded by the German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Nuclear Safety and Consumer Protection’s International Climate Initiative. The project aims to support developing countries in systematically assessing greenhouse gas emissions from transport, in analysing emission reduction potentials and in optimising the sector’s contribution to the mitigation target in countries’ NDC. TraCS feeds into other international cooperation projects run by the Government of Germany.

Coastal Railway ©Tharindu Nanayakkara/ Pixabay

Coastal Railway ©Tharindu Nanayakkara/ Pixabay

Nadja Taeger

nadja.taeger@giz.deVisit profile

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from X. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More Information