Electrifying vehicles offers an efficient way to decarbonise motorised transport. Apart from its positive effects on the climate – if powered with renewable electricity – it also reduces air and noise pollution and dependence on oil imports. So, it is not surprising that many countries aim at modernising their vehicle fleets with electric alternatives.

Electric car sales have skyrocketed over the last few years, reaching a global vehicle stock of over 10 million cars, up from virtually zero in 2010. During the pandemic, sales did not drop but merely slowed down in growth – unlike sales figures of their combustion counterparts. Electric car sales in 2021 represented 9% of global car sales, up from a share of only 2.5% in 2019. Much of this growth is driven by policies and incentive schemes, and the topic also features prominently in NDCs and LTS.

The development that we see in global sales figures also shows when comparing first and second generation NDCs. 53% of second generation NDCs (and 98% of LTS) contain measures related to electrification, compared to only 9% in the first round of NDCs in 2015. This shows that many countries pay more and more attention to the topic, in particular countries from the Global South: Electrification is covered in 55% of developing countries’ NDCs, while only 29% of industrialised countries referred to it.

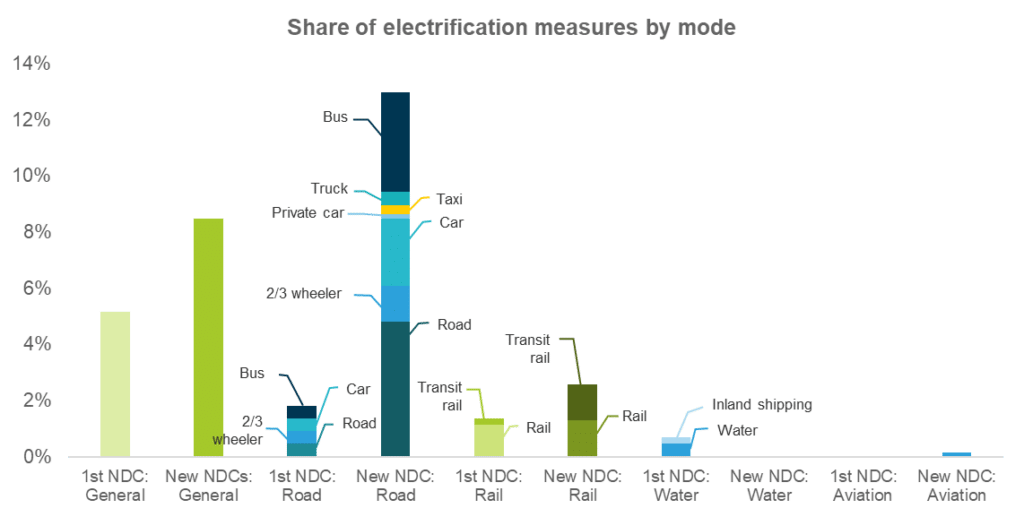

In new NDCs, the lion’s share of electrification measures target road transport, and mostly in relation to passenger transport. Electrification of rail receives limited attention, although it must be added that in many countries large shares of rail are already operating electrically. The electrification of ships or airplanes is not mentioned in NDCs; and only 1% of LTS documents include references to these sectors.

Cars are not always the best way to start electrifying the system. In countries with relatively lower consumer purchasing power – such as Chile, China and India – the electrification of public transport and urban freight may be prioritised over private vehicles. Higher private electric car ownership rates can be sought as a broader range of more affordable electric vehicles become available in the country. Similarly, the electrification of two- and three-wheelers is much easier, with lower initial investment needed for the replacement of vehicles. This is good news for many African and Asian countries where two- and three-wheelers are the primary means of transport.

We see much of this reflected in global sales data as well as in NDCs and LTS. There is substantial coverage of electric busses, all in climate policies of developing country, and two- and three-wheelers, most of these in the Asia-Pacific region.

However, most countries make very general statements about their intentions to support electrification, only sometimes supported by electrification targets. The lack of detail makes it difficult to assess the level of determination with which countries plan to move to implementation. 23 countries (18%) have set some form of electrification target in their new NDCs, and 10 countries (22%) in their LTS. Targets range from achieving “a share of 2% in the vehicle fleet by 2030” to “100% of new sales being electric by 2030”. Alternatively, countries include vehicle fleet targets, often for public fleets or public transport.

In new NDCs, 18% of measures discuss direct electrification and another 6% of measures refer to other alternative fuels, mostly biofuels and general mentions of ‘renewable energy’. Only 8 NDCs (6%) mention hydrogen as a potential option for the transport sector, but most stress that this is still under development. At the same time, 29 LTS (63%) see hydrogen as an option, with many focussing on trucks, ships and aircraft. Synthetic fuels only feature in the long-term visions and are mostly relates to shipping and aviation. Based on the great gap between NDCs and LTS, it seems that countries see hydrogen as a long-term solution rather than as a short-term action.

Electrification will only deliver true decarbonisation if the power consumed is generated with renewable energy sources. There is little mention of the considerable increases in electricity demand that will result from electrification, especially for the hydrogen production to fuel waterborne and airborne transport as well as heavy-duty trucks. Today still, transport has the highest reliance on fossil fuels of any sector (IEA, 2022). Additional power capacity based on renewable energy is needed to meet not only the current and future electricity demand from households and industry, but to also cater for future electricity demand from transport. Climate policies, however, neglect this so important linkage between transport and energy: only very few NDCs include explicit renewable electricity targets for the transport sector or link electrification targets to renewable power targets.

A recent study found that to achieve net-zero carbon emissions, renewable capacity investments of around US$ 12.4 trillion would be required to provide the clean power for electric fleets in Japan, China and the Republic of Korea alone. This might sound daunting, however, one needs to keep in mind that this investment would be spread over the next 30-40 years and represents manageable shares of GDP. The figure shows that the task of decarbonising transport does not stop at replacing vehicles, and it also highlights the need to be as efficient as possible in the choice of mode as well as for each individual vehicle in order to minimise any additional electricity demand. Designing incentives and charging infrastructure around shared mobility and public transport, automated where possible, will provide the largest benefits for a clean and efficient transport system and could save US$ 5 trillion annually by 2050.

| ProQR: Climate-neutral alternative fuels for aviation Brazil has huge potential in terms of renewable energy – and a rapidly increasing demand for fuel. The project has developed an international reference model for the production and application of climate-neutral fuels, which are produced using wind and solar energy and used in aviation. Fuels are produced and used in a pilot project to prove their feasibility and economic efficiency. Read more here. |

This blog article is part of a series of five blog articles around transport in new and updated NDCs and LTS based on an assessment by GIZ and SLOCAT and funded by the International Climate Initiative (IKI) of the German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Nuclear Safety and Consumer Protection. For a comprehensive overview of further aspects of the assessment take a look at our brochure. The blog series follows recommendations for policymakers on how to enhance climate ambition in transport (available here).

Check out our other blogs in this series:

Navigating the steep curve towards a paradigm shift: discussing the level of ambition of transport-related targets. Published on 01 December 2021

Resilience on the slow lane: discussing the efforts to enhance resilience of the transport sector and adapt to already existing and future climate change impacts. Published on 14 December 2021

Empowering cities with national support?: discussing how national governments can support cities in their efforts to transform their mobility systems – and whether climate policy documents reflect this. Published on 11 January 2022

On January 25, we took a deeper look at the role of freight transport in NDCs and LTS.

Nadja Taeger

nadja.taeger@giz.deVisit profile

Marion Vieweg

marion.vieweg@current-future.orgVisit profile

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from X. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More Information