To achieve sustainable mobility, we must integrate the experiences and realities of the half of the population that has not been included: women. This edition of #StoriesofChange explores Latin American cases.

At first, we could take is as read that the goal of climate action is to reduce emissions. But to achieve this, we became aware that we must transform the world as we know it. We also had a better understanding that the world and people are diverse. Different realities come across us. Understanding this is the first step when we talk about gender and mobility.

Feminist movements in recent decades have shown us how gender is a conditioning factor that is reflected in different areas of human life, including the way we move across cities.

As a social construct that associates a person’s biological sex with attitudes, feelings and behaviours in a certain culture, gender is also relates to social roles and identities that have constructed an inequality that mainly affects women.

But these differences are not universal. Other perspectives have allowed us to understand that we cannot speak of a universal experience of women, but that aspects of race, class, age, place of origin, among others, are also involved.

For instance, the women most exposed to the effects of climate change live mainly in rural areas[1]. Recognising that urban mobility is not gender neutral, we at GIZ have made efforts to integrate this vision to achieve diverse and fair cities for women and girls. While working on the topic globally, this is part of what we have achieved in Latin America.

Transport is about connecting people, giving them access to opportunities. It is an area of work with a very nice social sense.

Carolina Simonetti, General Manager of the Chilean Airline Association

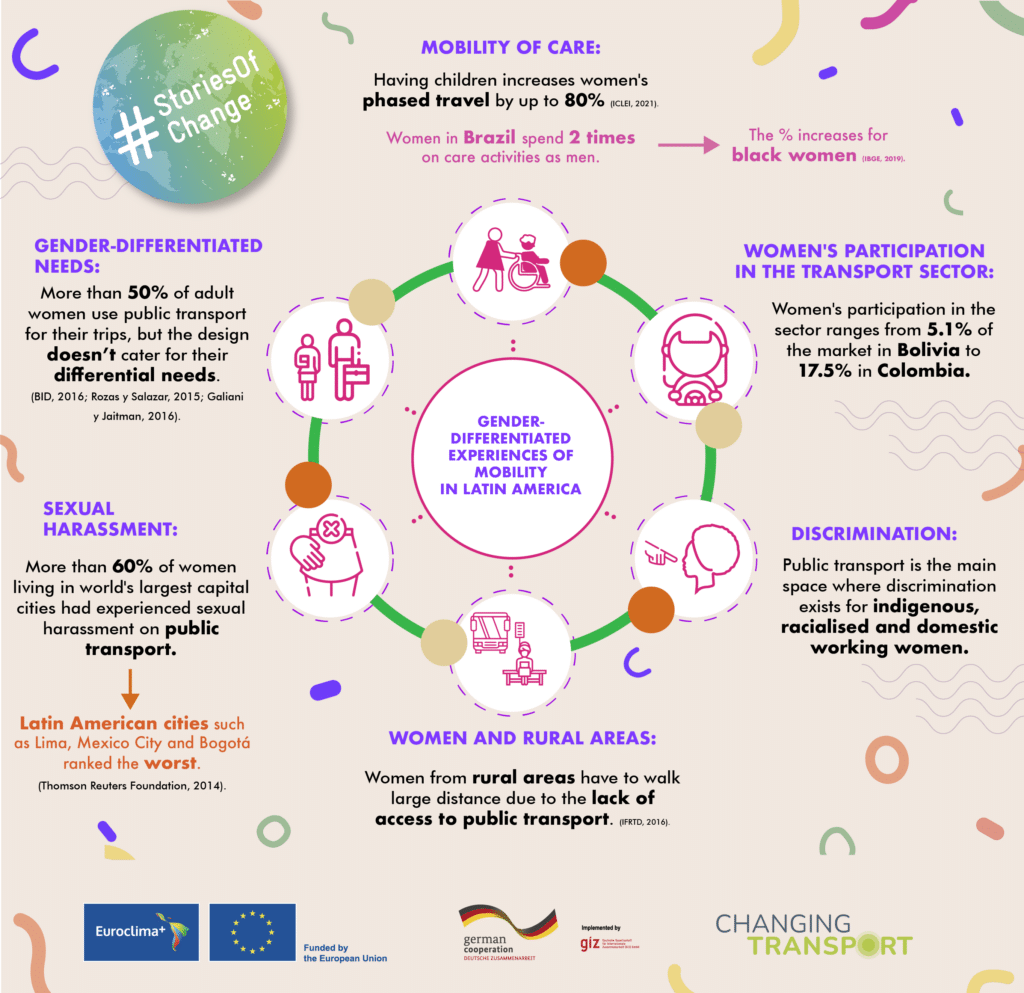

Latin American cities do not differ from other cities in the world in terms of gender inequality. Current urban mobility systems are inadequate to the routines and needs of women, despite the fact that they are the main users of public transport. We build cities based on an apparently neutral model, but which in reality is closer to male needs.

Let us remind ourselves that travel routines and needs are also social constructions. Women are responsible for care activities: shopping, taking children to school, accompanying family members to medical visits. These activities have historically been relegated to women and current mobility planning does not take into account these trips, which are done in a staggered manner.

Cities are built without taking into account the movements and spatial requirements of women and their caring roles, we need to create spaces for us and our experiences.

Ana Lucía González, Deputy Mayor of Montes de Oca, Costa Rica

There are other problems related to gender inequality: sexual harassment in public transport, insecurity in public spaces, pavements not designed to carry children and strollers, buses without adequate infrastructure to meet women’s needs.

In addition to this, there are other complex problems that Latin American women experience: urban areas where public transport is inaccessible, expensive or far away from the experiences; racism and discrimination in public spaces, long distances and high transport costs between the periphery and the centre of the cities, which mainly affects women domestic workers, among others.

The lack of gender mainstreaming and women’s participation in the sector is a social problem with environmental consequences. The COVID-19 pandemic contributed to a distrust of sustainable mobility modes. This has resulted in sustainable mobility alternatives being displaced by individual motorised travel.

Women do not feel safe to make walking trips and there is inadequate infrastructure for care trips. There is a gender gap between men and women in cycling skills and in the perceived safety of cycling infrastructure. Public transport does not cover the types of journeys women make, nor does it comprehensively address the problems women experience when using public transport.

We must change this scenario.

Making cities suitable for women and girls requires including a gender perspective in policies, plans, and projects. These are some of the initiatives that we at GIZ have implemented through the EUROCLIMA+ programme:

Colombia’s National Urban Mobility Strategy (ENMA in the Spanish abbreviation) is an important reference for other countries in the region, as Colombia is the country with the most bicycle trips and bicycle lanes built in all of Latin America.

The ENMA seeks to reduce the effects of climate change and GHG emissions by promoting active modes (walking and cycling) through an action plan which responds directly to the NDC commitments of the transport sector. This policy assumes the mainstreaming of the gender and differential and differential approach as vital components.

By incorporating this approach, we enable more robust analyses and recognise people’s different experiences and needs for moving. Therefore, the ENMA places particular emphasis on improving mobility conditions for women, children, adolescents, older adults and older adults and people with disabilities with disabilities.

With the MobiliseYourCity methodology, we have promoted Sustainable Urban Mobility Plans in Latin American cities. Currently, Ambato (Ecuador), Antofagasta (Chile) and Guadalajara (Mexico) already have robust planning to implement measures in their territories aimed at environmental, social and financial sustainability in their mobility systems.

In these projects, the inclusion of a gender perspective during the diagnostic phases – such as travel surveys, territory studies and analysis of transport routes – allowed to build a broader vision of the dynamics of people’s mobility and highlighted the gap that exists with respect to women’s needs for mobility.

In the case of Ambato, its SUMP contains the packages of measures “Programme for the reduction of inequality, poverty and gender gaps in transport” and “Programme for the improvement of rural accessibility and specific populations”.Guadalajara’s SUMP includes, in its integral packages, “Mainstreaming aspects of gender perspective, inclusion and diversity in mobility studies and works”. On the other hand, the SUMP of Antofagasta identifies gender gaps within the social aspects of mobility, which will be comprehensively addressed in its packages of measures on public transport or land use and public space, for example. Furthermore, in its measure “Creation of a regional metropolitan transport corporation”, the work plan explains that a Mobility Policy with a Gender Approach will be elaborated in short term.

These learnings will be disseminated in a publication to be launched in the middle of the year entitled How to integrate a gender perspective into SUMPs: Lessons from Latin American cities.

Indigenous women are the main users of the tuc tucs in San Juan Comalapa, a municipality in Guatemala where the majority of the population belongs to the Kaqchikel indigenous community.

In this pilot project, we provide electric units and the installation of charging systems with a focus on social transport. The units were designed to meet the needs of women not covered by conventional tuc tucs: they are comfortable to ride in, have more space for carrying packages and large objects. In addition, some units are for the exclusive use of older adults, children and people with disabilities.

Historically, the transport sector has low women participation. For example, in Latin America, the participation of women in the transport sector ranges from 5.1% of the market in Bolivia to 17.5% of the total employees in the transport sector in Colombia.

Broadening women participation is the key to change the standards of urban infrastructure provision, from the inclusion of women in jobs that are not traditionally occupied by them, such as bus driving, operation of transport system and institutions responsible for urban mobility services.

Women networks in transport are therefore key to boost women participation in this sector. In Latin America, the outstanding network is Mujeres en Movimiento (Women in Motion). Also in Asia, the Women on the Move network promotes women’s engagement in male-dominated sector, developing peer-to-peer format for dialogues on gender equality and recently set up a mentoring programme to inspire and encourage women in the region to actively transform the transport sector in their country.

To contribute to changing this context, EUROCLIMA+ has supported two editions of the programme “Urban Women Leaders”, a leadership program co-created by Women in Motion (WIM) and the Bernard Van Leer Foundation.

Direct beneficiaries of the EUROCLIMA+ programme participated in the training, from Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Paraguay and Uruguay. As a final activity for the 2022 edition, participants developed an UM intervention to address local challenges for promoting gender inclusive cities. The projects are available on the WIM website.

We know that the path to reduce the gender gap in mobility is still enormous. However, learning from these experiences has allowed us to synthesize these lessons and we will seek to replicate them in other contexts in the region.

At GIZ we lead the community of practice “Sustainable Urban Mobility Platform in Latin America”, an initiative to promote the exchange of knowledge and the creation of synergies in the region. One of our objectives is the mainstreaming of the gender approach in the activities of this platform.

Gender mainstreaming will be present not only in future projects, but we will continue to promote the topic in activities such as workshops, trainings, dissemination of information, exchange and networking spaces.

Mobility in our cities will never be truly sustainable if we do not continue to integrate the diverse experiences of half of the population. The facts have shown that doing this has a positive impact for all people.

There was a moment when I understood that my actions and words spoke not only of mobility but also of representation and the presence of women in this sector. There I understood that I had to integrate gender issues as an essential part of my actions.

Jone Orbea, leader of the MOVE Programme, Electric Mobility in Latin America and the Caribbean, UNEP

[1] UNFCCC. New Report: Why Climate Change Impacts Women Differently Than Men | UNFCCC, 2022.

If you believe that you suffer (potential) negative social and/or environmental consequences from IKI projects, or wish to report the improper use of funds, to voice complaints and seek redress, you can do so using the IKI Independent Complaint Mechanism.

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from X. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More Information