Electric mobility is gaining momentum in Kenya. Report on the Analysis of the Current Battery Ecosystem in Kenya highlights that there will be 150 metric tonnes of Li-ion batteries retired from traction applications by 2030. However, key questions that remain for many electric vehicle (EV) owners and enthusiasts are;

What happens when the battery reaches the end of its life? Can it be replaced? And what becomes of the retired battery?

At the heart of every EV is the high-voltage battery, the equivalent of a fuel tank, only far more complex and valuable. It determines driving range, vehicle performance, and long-term resale value. Modern EV batteries are predominantly lithium-based, valued for their high energy density and declining costs. However, the materials they rely on, that is, lithium, cobalt, nickel and others, are finite. Ensuring these resources are used efficiently is why battery circularity is so important.

Battery circularity focuses on maximizing the economic and environmental value of a battery throughout its entire lifecycle, from vehicle use to eventual recycling. It ensures batteries operate safely for as long as possible and that, once retired, their valuable materials are recovered for future production.

This approach is critical for resource conservation, environmental protection and economic value.

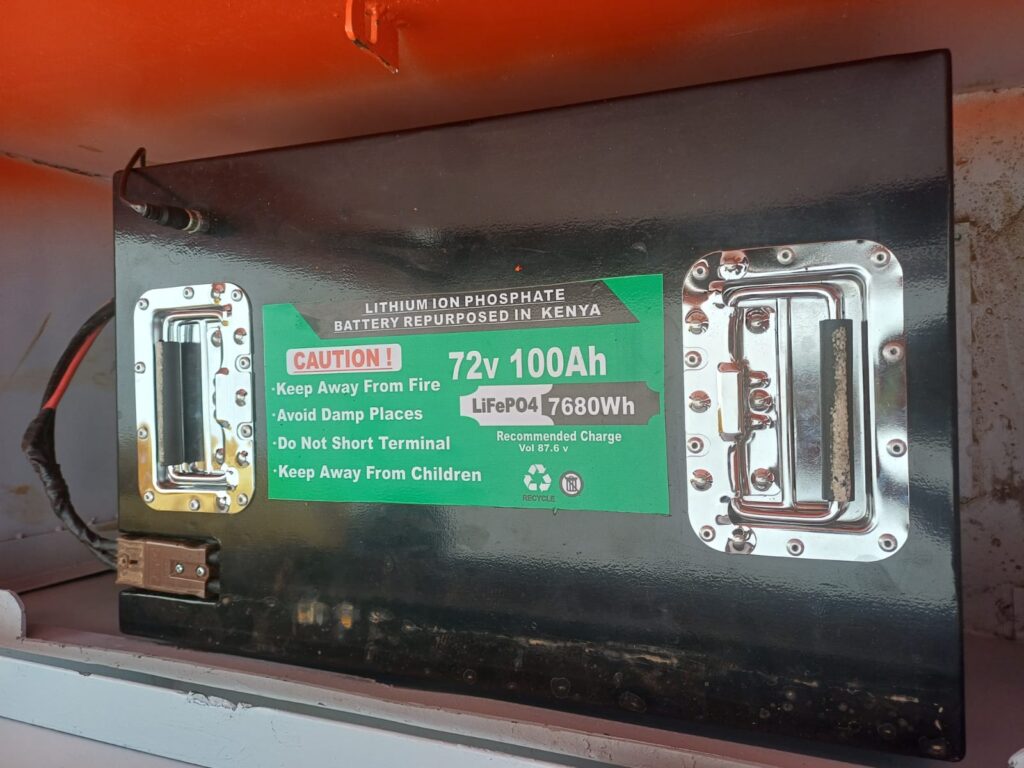

An EV battery is typically retired from automotive use when its state of health (SOH) falls to around 80 percent. While this may no longer meet vehicle performance requirements, the battery still retains significant usable capacity. This is where second-life applications emerge, and in Kenya, a growing number of companies such as Knights Energy, Enviroserve , Acele Africa are already deploying retired EV batteries to enhance energy access in remote areas and to complement the national grid.

Depending on its condition, a retired EV battery may be repurposed in several ways. It can be reused as a complete pack for stationary energy storage, disassembled into modules and reconfigured for new voltage or capacity needs, or broken down into individual cells for more targeted reuse.

Before repurposing, batteries undergo rigorous testing. Parameters such as usage history, internal resistance, thermal behaviour, charge and discharge limits, remaining capacity and structural integrity are assessed to ensure safety and reliability. Only batteries that meet strict criteria are approved for second-life use.

Today, as highlighted in Exploring Second-Life Application of EV Batteries in Kenya, second-life batteries are increasingly deployed in home and commercial energy storage systems, solar mini-grids in remote communities, backup power solutions and micro-mobility or low-speed electric vehicles. With proper system design and safety controls, these applications can extend battery life by many years beyond its initial automotive role.

Eventually, every battery, whether in its first or second life, reaches a point where reuse is no longer viable. At this stage, recycling becomes essential. Recovering lithium, nickel, cobalt, copper, and aluminium ensures these materials re-enter the manufacturing cycle instead of ending up in landfills.

However, collecting batteries for recycling presents challenges, particularly when second-life systems are widely distributed or located in remote areas. To address this, several strategies are emerging. Internet-of-Things (IoT) – enabled tracking systems allow continuous monitoring of battery health and location. Kenya has enacted Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) regulations under the Sustainable Waste Management Act No. 31 of 2022 and Legal Notice No. 176 of 2024, to ensure manufacturers remain accountable for end-of-life recovery. Meanwhile, Battery-as-a-Service (BaaS) models as done by some electric two wheelers companies in Kenya retain battery ownership with specialized firms, simplifying collection and recycling logistics.

A common concern among EV owners is what happens to the vehicle once its battery is removed. The answer depends on the battery’s condition and the chosen pathway.

If diagnostics reveal that only a few modules or cells are degraded, partial replacement is possible. Faulty components can be replaced, the pack rebalanced, and the battery reinstalled after validation.

In cases where the entire pack is degraded but suitable for second-life use, full reconditioning may occur. The old pack is repurposed, and the vehicle is fitted with a newly built battery using fresh cells in the original casing, along with a reprogrammed Battery Management System (BMS) and updated vehicle firmware. While technically demanding, this process can significantly extend vehicle life and performance as highlighted through this report.

Alternatively, owners may opt for a brand-new OEM replacement battery, especially when the old pack is fully redirected to second-life applications.

Battery circularity is more than a technical concept; it is a roadmap for sustainable electrification. By extending battery life, enabling second-life applications, and ensuring responsible recycling, circularity keeps EVs affordable, reduces environmental impact, and preserves valuable materials within the supply chain.

With the right systems, policies, and innovations in place, an EV battery can truly complete the circle – from the road to the grid, and ultimately back into the next generation of electric vehicles.

Promotion of electric mobility in Kenya project is implemented by GIZ in cooperation with the State department for transport and funded by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) with cofinancing from the European Union.

Battery Technology training at Knights Battery Testing Centre Kenya, Source: GIZ by Carol Mutiso

Battery Technology training at Knights Battery Testing Centre Kenya, Source: GIZ by Carol Mutiso

Cynthia Kipsang

cynthia.kipsang@giz.de

Visit profile

Cyprian Sulwe

cyprian.sulwe@giz.de

Visit profile